I was saddened to learn today that designer Kate Spade died by suicide at age 55.

In addition, I was appalled by much of the news coverage, which failed to follow readily available guidelines for reporting on such deaths.

In 2014, I blogged about suicide and mental health issues after another designer, L’Wren Scott, died. A lot of what I said is relevant to Kate Spade, so I’m reposting the entire thing below — just keep in mind that the business elements don’t apply specifically to Spade, who sold her remaining stake in her namesake company for a profit over 10 years ago. I’m leaving those paragraphs in, however, as a reminder that the reasons for a suicide are often more complex than they might seem to people who didn’t know the deceased personally.

UPDATED THURSDAY, JUNE 7, 2018, TO ADD: Here is the full statement from Kate Spade’s husband, Andy. Continue reading below for my L’Wren Scott post.

FROM MARCH 21, 2014:

I’ve been so troubled by the suicide of designer L’Wren Scott that I’ve been tongue-tied for days. Also, I didn’t know her; I don’t even know anyone who knew her; and I don’t want to presume to know anything about her state of mind. However, other people have no such qualms and some general misconceptions about both business and depression that I’ve seen in news coverage and public commentary have been nagging at me so much that I have to say something.

Losing money isn’t necessarily a sign of long-term failure in any industry. Huge public companies post giant losses all the time. Twitter is a good example. In the last quarter of 2013, the company reported a net loss of over half a billion dollars. Like a lot of big companies, Twitter reports adjusted earnings that are supposed to more accurately reflect its operations by excluding things like one-time writedowns. (When companies play that kind of accounting game, it’s often the adjusted number that the stock market is going to react to and that’s why I said I had to look for the “most meaningful numbers” at my old job rather than “net profit or loss.”) According to the adjusted report, Twitter made $10 million in the fourth quarter of 2013. For the year ended Dec. 31, 2013, Twitter lost over $645 million. Even the adjusted report showed a loss of over $34 million. What did Twitter’s chief executive officer, Dick Costolo, say about this? “Twitter finished a great year with our strongest financial quarter to date.” (That would be the strongest quarter since Twitter launched in 2006 — the same year Scott started her business.) Are any of you avid Twitter users saying, “God! Twitter is the most stupid idea EVER!” because of this? And what the market cared about was Twitter’s potential for growth, not the bottom line. There is a lot more to understanding any business, big or small, than one number.

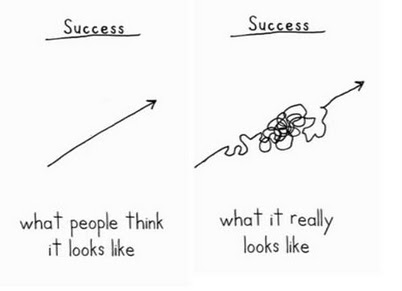

Also, I resent anyone saying that Scott was some kind of fraud because she used Instagram to share attractive pictures of her enjoying a luxurious lifestyle that her boyfriend, Mick Jagger, was happy to pay for. In fact, I’ve always been irked by the general criticism that people are editing themselves to show their best sides on social media. Of course, you edit yourself! We edited ourselves before social media! If the person who delivered your mail pre-Facebook asked, “How are you?” did you reveal the darkest part of your soul, your business worries, your family problems, or point out your giant pimple or new wrinkle? I hope not, because no one is obligated to go around like a raw wound, exposing personal agonies to the entire world. When it comes to business, you’re a fool if you don’t create an aura of success. You’ve got to show confidence in yourself if you want others to have confidence in you, so I strongly advise any of you entrepreneurs to fake it till you make it. And if you don’t make it, fake it right up until the day that you go out of business. Fashion writer Cathy Horyn, who wrote one of the most thoughtful tributes to Scott, said she learned that Scott did plan to close her business this week. A business closure is no reason to look down on an entrepreneur. It sucks for the person doing it, obviously. No one enjoys a setback. But it happens all the time, to a lot of people … and to a lot of successful people, sometimes multiple times. As Arianna Huffington has said, “Failure is not the opposite of success.” It’s part of success.

Unfortunately, all of these points are impossible to comprehend if you’re depressed. I’ve seen comments that L’Wren Scott had nothing to be depressed about, but depression is a disease that, like diabetes or cancer, doesn’t distinguish between rich and poor, famous and totally unknown. If you’re depressed, you don’t have delusions and hallucinations like you do with schizophrenia but, more and more, I realize how much depressed people are out of touch with reality. The depressed person is sure his or her every action is catastrophic, and equally sure that everyone else is effortlessly achieving perfection. I speak from my own personal experience and the experiences of those near and dear to me. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard people cry to me, sincerely meaning it, “If I don’t do XYZ, this is THE END for me!” and I’ve said it a thousand times myself. The one time that stands out most in my memory was in 2009 or so. I’d muddled through the death of my business partner in 2006, then restarted and renamed my business right in time for the global economy to collapse in 2008, followed by the tripling of gold prices. I was bawling to a therapist that I couldn’t close my business, I just COULDN’T, because my whole life would be RUINED. (I was always saying such things when nothing particularly bad was happening, so anything objectively wrong pushed me to the edge.) The doctor asked, “Really? Would it mean your whole life was a failure? Would you think someone else’s life was worthless if she or he closed a business?” I grudgingly had to admit — not on the spot but a few weeks later — that I wouldn’t judge anyone else so negatively. In fact, I knew and admired people who had closed more than one business. And then the doctor got me to admit that if I had to close the business, that I would be sad and disappointed and then … I would do something else. No one was shutting out other options except me. It might have been the first time in my life I realized that my mind was playing tricks on me. Depression was more than a bad mood; it was about seeing patterns, making connections and reaching conclusions that weren’t true.

There were plenty of times that logic wouldn’t make any impression on me, but, for some reason, it did then. Now I always resort to logic when I’m trying to convince someone to get treated for their depression. I’m very big on treatment. I vote for it early and often. Depressed people resist it because they’re so sure they’re seeing the truth, and how can you treat the truth? Plus there’s the concept that we should all be able to use willpower and “snap out of it.” I know that type of thinking, so when I hear people talking illogically about themselves, I try to convince them that their “truth” is a lie told by a disease, and diseases can be treated. Speaking of truth and treatment, in 1993, a psychiatrist named Peter D. Kramer wrote Listening to Prozac, which questioned whether Prozac — approved for treatment of depression in 1987 — changed people’s legitimate, true characters in a trivial, “cosmetic” way. He worried it was some kind of performance-enhancing drug for the personality, used by folks who want to get ahead at work, for instance, by becoming medically more gregarious. That’s the kind of pejorative, “you’re doing it the easy way” attitude that scares genuinely depressed people away from appropriate treatment to this day. A patient who finds the right antidepressant (it’s not the same medication for everyone, nor does everyone need medication) will learn that it’s the sick, depressed thoughts that are false, obscuring the true personality the way clouds hide the sun. The sun is still there, you know. It’s a tragedy when depression convinces someone that the light is gone forever.

If everything seems dark, click here for The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

UPDATED AT 1 PM, MARCH 21, TO ADD: A spokesman for L’Wren Scott’s company told WWD the reports about financial condition of Scott’s business are “highly misleading and inaccurate” and that the company is “fully able to meet … liabilities and pay all suppliers and customers.”

In a statement, the spokesman said:

“Ms. Scott was considering a re-structure of her global business. The L’Wren Scott business consists of a wholesale business of ready-to-wear women’s wear, a bespoke Couture business for private clients, a licensing business, Ms. Scott’s globally recognized work as a fashion consultant and stylist and her collaborations such as her recent collection for Banana Republic.”

The statement went on to point out that this was a young company:

“Her business overall was only seven years old and although some areas of the business had not yet reached their potential other parts of her business were proving successful. As a private business, details of income and turnover are not publicly disclosed, however it can be said that the long-term prospects for the business were encouraging.”

The link to WWD’s full story here, but WWD is subscription-only.