Several newspaper articles this weekend struck a chord with me.

In the New York Times magazine, David Amsden wrote about New Orleans-born John Cummings, a white 77-year-old “trial lawyer who has helped win more than $5 billion in class-action settlements and a real estate magnate whose holdings have multiplied his wealth many times over.” Cummings bought the Whitney Plantation, located 35 miles west of New Orleans, and has spent more than $8 million of his own money renovating it for the past 15 years. Instead of recreating the old property as an antebellum beauty spot for weddings and special events, Cummings dug into the plantation’s ugly past in order to turn it into America’s first slavery museum. The Times says “the results are both educational and visceral,” immediately bringing to my mind Holocaust museums, which we do have here in the U.S. In fact, the story quotes Columbia University historian Eric Foner — whose class I took in the 1980s — on that very topic. As he told Amsden:

“It’s something I bring up all the time in my lectures … If the Germans built a museum dedicated to American slavery before one about their own Holocaust, you’d think they were trying to hide something. As Americans, we haven’t yet figured out how to come to terms with slavery. To some, it’s ancient history. To others, it’s history that isn’t quite history.”

The plantation was originally built by the Haydel family, German immigrants who ran the property from 1752 to 1867. Amsden wrote:

“In 1835, a biracial child named Victor was born on the grounds of the Whitney, the son of a slave named Anna and Antoine Haydel, the brother of Marie Azelie Haydel, the slaveholder who ran the plantation at the time. One hundred and seventy-nine years later, a group of both the black and white descendants of the Haydels made their way to the Whitney’s opening in December. Many were meeting for the first time, and the sight of them embracing and marveling at the similarities in their appearances was as powerful as any memorial on the plantation.”

Cummings is still finishing up a memorial to victims of the German Coast Uprising, which Amsden calls “an event rarely mentioned in American history books.” That’s for sure. This was the first time I read about a punishment that you’d normally associate with the Spartacus-led slave uprising of ancient Roman times. Here is the shocking description:

“In January 1811, at least 125 slaves walked off their plantations and, dressed in makeshift military garb, began marching in revolt along River Road toward New Orleans. (The area was then called the German Coast for the high number of German immigrants, like the Haydels.) The slaves were suppressed by militias after two days, with about 95 killed, some during fighting and some after the show trials that followed. As a warning to other slaves, dozens were decapitated, their heads placed on spikes along River Road and in what is now Jackson Square in the French Quarter.”

Cummings has done a great thing by exposing this. Click here to read the whole story (subscription required).

A hundred and ten years after the German Coast Uprising and almost 60 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, another horror took place. This one was also left out of my childhood history books even though it was one of the deadliest incidents of racial violence in U.S. history: the Tulsa, Okla., race riot of 1921. After a young black man was accused of raping a young white woman, violence broke out, resulting in over 100 deaths and the well-off African-American Greenwood section of Tulsa being burnt to the ground. This came up in Mara Gay’s Wall Street Journal story about 100-year-old Olivia J. Hooker, a retired Fordham University psychology professor who is being honored by the U.S. Coast Guard. In 1945, she was the first black woman to enlist in the Coast Guard. Dr. Hooker was six at the time of what she calls “The Catastrophe” and remembers men with torches coming into her family’s backyard and setting fire to doll clothes hung out to dry before they ransacked the house. “I still don’t know why they bothered to burn up a little girl’s doll clothes, but they did,” Dr. Hooker said.

Click here to read Dr. Hooker’s story.

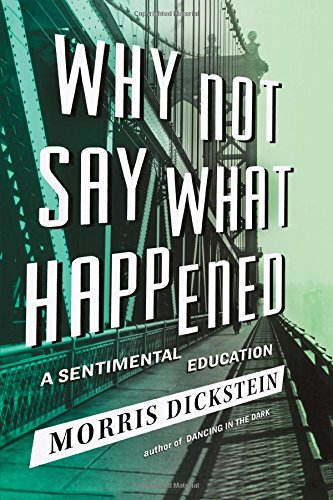

On a happier note, Professor Morris Dickstein has a new memoir out called Why Not Say What Happened. (That title also applies to the historical events mentioned above, no?) It was reviewed by both the New York Times Sunday Book Review and the Wall Street Journal, which is no mean feat these days. The memoir covers Morris’s undergraduate years at Columbia University, as well as his experiences there as a professor between 1966 and 1971, an era that saw the famous 1968 student protests against the Vietnam War. I know Morris because of his decades of service as a trustee of the Spectator, Columbia’s undergraduate news organization. When I took over as chairman of Spec’s board of trustees in 2008, Morris was ready to retire, but he stuck it out for six extra years as the organization dealt with the fallout from the recession and tremendous changes in the news industry. I’m so thankful that he stayed! Morris is truly a pleasure to work with. Click the image below to buy his book on Amazon!

The Cummings article is amazing. Having visited one the “antebellum beauty spot” plantations, where we were told there were once slaves but we couldn’t see any sign of it, I would much rather visit The Whitney plantation.

I would really like to see it!