Post-Covid, I can’t write or even think about 9/11 as I once did. I see that many people feel the same — these comments were among those that caught my eye:

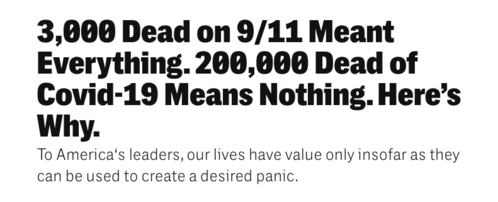

On 9/11 in 2020, I wrote of my horror at this lack of perspective when the Covid death toll passed 200,000. A piece Jon Schwarz wrote for the Intercept resonated with me.

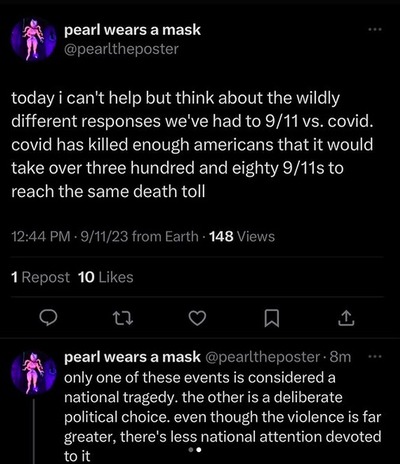

Little did I know that three years later, the Covid death toll would be 1,140,278 in the U.S. alone, and we’d still be arguing over vaccines and masking.

This comparison does nothing to diminish my personal grief over 9/11, of course, or the grief of everyone individually affected — whether they lived through that day or had their lives permanently altered by it even before they were born (at least 100 children were born after their fathers died in the attacks, and an untold number of people who died in the post-9/11 wars weren’t alive on 9/11/2001). Instead, that pain increases my compassion for anyone suffering a tragedy. But I don’t see that happening on a societal level. What do words like “Never Forget” mean when there’s a percentage of this country that responds to any other mass death with defensiveness, victim-blaming, and willful amnesia? Whether the death toll from a particular incident is much smaller than 9/11 (like the 19 children and two teachers murdered in Uvalde, Texas, last year) or much larger, like the Covid death toll or the annual gun-violence death toll (2023 currently stands at 30,111 deaths from both homicide and suicide), nothing unites us in an effort to challenge the status quo.

Even American deaths related to 9/11 are given short shrift compared to the deaths suffered that day. There were nearly 7,000 U.S. military deaths in the post-9/11 wars waged upon Iraq and Afghanistan (countries that had nothing to do with the terror attacks but which lost hundreds of thousands of civilians due to American wars). The Uniformed Firefighters Association says that 341 New York City Fire Department firefighters, paramedics and civilian support staff have died from post-9/11 illnesses — almost equaling the 343 first responders killed that day. Civilians have also suffered fatal illnesses. One of them was someone I knew: Wall Street Journal editor Rich Regis, who was standing next to my husband as the Twin Towers collapsed. Regis suffered dire immune-system problems for nearly 20 years; it was only shortly before he died in 2020 that doctors found small silicone tubing from the World Trade Center in his airway. Yet Republicans have repeatedly voted against funding health care for 9/11 survivors, saying the $10 billion cost was too high. For comparison, a study at Brown University put the cost of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan at $8 trillion. It would be laughable if it wasn’t completely tragic.

Today, I’ve been wondering if the nation only cared about 9/11 because it was so shockingly visual and public. Property was destroyed — people always care about the well-being of buildings in America — and “foreigners” were conveniently to blame. An attack from the outside was and is a massive affront to our pride. But when we cause our own less-televised disasters and have no scapegoats, we as a society seem to decide the victims don’t matter as much as our comfort.

I feel like I wrote about the nuances of 9/11 more eloquently for the 20th anniversary. (Here are Part I and Part 2 of that piece.) As a result, I wasn’t planning to write anything today, but I looked at the anniversary blog and decided the way I ended the second part is worth repeating now:

“… despite everything, the righteous thing to do is never give up. Don’t give in to the prevailing attitude that other people’s lives don’t matter. Do what is within your ability to set a better example. As lawyer/activist Florynce Kennedy said, ‘You’ve got to rattle your cage door. You’ve got to let them know that you’re in there, and that you want out. Make noise. Cause trouble. You may not win right away, but you’ll sure have a lot more fun.‘

We can do better. We must do better.