British fashion designer and outspoken climate- and human-rights activist Vivienne Westwood died at age 81 yesterday. During her 50-year career, Westwood pioneered punk, then pivoted to history-driven high fashion that provoked critics almost as much as her bondage pants did. She never caved to convention. Even in 1992, when Westwood was so established that Queen Elizabeth II awarded her the Order of the British Empire, Westwood accepted the honor at Buckingham Palace looking perfectly tailored while going “knickerless” — as a twirl before the press made clear.

I’ve already read dozens of Westwood tributes, and the one that’s most captured my imagination, most succinctly, is from The Other Lagerfeld account on Instagram. After applauding Westwood’s use of fashion to deliver serious messages, they wrote:

“Vivienne was collected fun in one place. She was a creative mess of a genius. Vivienne was just a fucking vibe. Her energy was unmatched; it was crazy yet vibrant yet cool yet energetic yet in the same time philosophical. Vivienne was the architect of punk and the architect of messy Haute Couture.”

“Just a fucking vibe!” I love it! That’s exactly what it was when supermodel Naomi Campbell took a famously giggly tumble off Westwood’s nine-inch-high platform shoes on the designer’s Fall/Winter 1993 “Anglomania” runway.

And “just a fucking vibe” was definitely generated by the store(s) Westwood ran in the 1970s with then-boyfriend Malcolm McLaren, the eventual manager of the Sex Pistols. Westwood and McLaren first opened as Let It Rock in 1971, selling ’50s memorabilia and making Teddy Boy-style skinny trousers. The shop name then evolved along with the punk music and fashion scene it simultaneously drew from and created. Vogue has the list: “Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die in 1972, SEX in 1974 (with the introduction of fetishist rubber dresses, nipple clamps, and spike shoes), Seditionaries in 1976, and finally World’s End in 1979.”

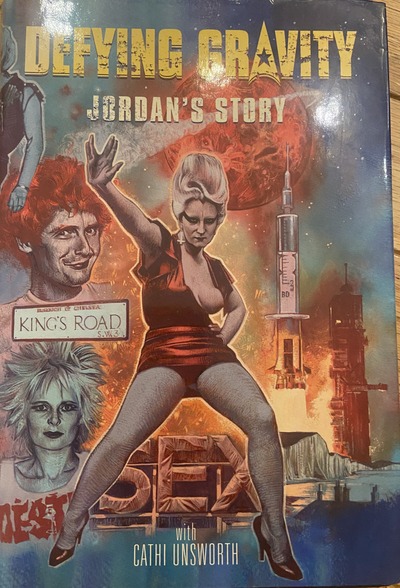

“We tried to present a feeling that the shop was a place that, if you had the guts to walk in, you could just hang out. Like the coffee shops of the 1950s, or the cafes of Prague, where philosophers would go to chew things over,” remembered Jordan Mooney, one of the key vibe-generating people in Westwood’s orbit in the punk era. Jordan, née Pamela Rooke, died this April at 66. When Paul Tierney of the Guardian interviewed her in 2019 about her memoir, Defying Gravity, he described her as “more than a shop assistant; she was the embodiment of the SEX aesthetic.”

However, Westwood and McLaren didn’t invent Jordan; when she walked into their store looking for a job, she was already deep into her idiosyncratic style, which was accented by a sky-high white-blonde beehive and either Mondrian-like makeup or the extreme eye makeup recently revived by actor Julia Fox. You can see Jordan, starting 36 seconds into this video about SEX, talking about how British Rail would upgrade her ticket to prevent her fashion from causing chaos to break out in the second-class cars.

While Jordan and her hair defied gravity, Westwood was the center of gravity, outlasting all her early collaborators and customers. The Sex Pistols broke up in 1978. Jordan left the scene in the early 1980s to become a veterinary nurse and cat breeder. McLaren and Westwood ended their personal and professional partnership in the early ’80s too. (After McLaren’s death in 2010, Westwood revealed that he had been abusive and that she hadn’t wanted a relationship with him.) Yet Westwood kept moving forward herself, and the influences that she had absorbed and re-imagined and spun back out to the world inspired generations of designers. While many creatives turn stale and smug with that kind of success, Westwood kept challenging the establishment that awkwardly embraced her — a fashion designer calling for slow fashion, she was beloved for her past philosophies while always advocating for new ones. She returned to Buckingham Palace in 2006 to accept a damehood from then-Prince Charles, wearing small horns for the occasion, but, again, no underwear. (The prince joked that he hoped the honor would help her career.) And she didn’t retire because, as she said in a 2012 interview, “… my job gives me the opportunity to open my mouth and say something and that’s wonderful,” before adding that the world had had enough of people like her. “A girl said to me recently: ‘I really want to be a fashion designer but I also like biology’. I said: ‘Do biology’.”

It’s most fun to learn about Westwood from Westwood herself, so if you have to read just one article, I recommend the 2012 interview with the Independent. It includes her response to the knee-jerk question of how a fashion designer can dare to talk about conservation. For a deeper dive into Westwood’s activism, there’s a 2007 Guardian interview about her 22-page climate activism manifesto, “Active Resistance to Propaganda.” By the time she presented the manifesto at Serpentine Galleries in 2008, she took issue with her own words. It had been, she said, a couple of years since she wrote, “Dear friends. We all love art, and some of you claim to be artists…”; now she asked, “Have we really got time to be art lovers?” (Those remarks from 14 years ago might help some readers contextualize the 2022 climate activism around famous artworks.) In addition, the online diary she started in 2010 is available as an eBook called Get a Life, and her self-titled memoir came out in 2014.

The BBC’s obituary is excellent — covering, among many other things, Westwood’s use of swastika imagery in the punk era, which is something I wrote about here in 2007. Of course, you should read the Vogue obituary. If you can find a way past the Times of London paywall — I never have — you can read the 2014 article “Mr and Mrs Vivenne Westwood,” and learn about Andreas Kronthaler, Westwood’s husband, co-designer and creative director. GQ’s 2000 interview with McLaren is free, except for the time you’ll spend wondering why anyone tolerated his toxicity for more than five minutes. On the brighter side, one of the few nontoxic things about social media is the sharing of personal stories, perspectives, and fan knowledge that would otherwise be missed, as I pointed out when I wrote about fashion editor Andre Leon Talley after his death early this year. One of my favorite 1980s It Girls, Dianne Brill, captured a charming moment with Westwood in a short Instagram post: “So many images running in my head. Like Vivienne showing me a jacket she made that looked like a tailored jacket non stretch but had no seams. Her excitement at accomplishing that was through the roof.” Johnny Valencia of Pechuga Vintage, who worked for Westwood for six years starting in 2012, wrote a longer tribute, including:

“I wore diamanté horn tiaras with tiny orbs, paired with ‘Drunken’ trousers and mile high platforms because my boss, Vivienne Westwood, said it was OK. And for once in my life I felt accepted. I was home. And this is the effect that Westwood had. You weren’t just wearing clothes. You were wearing impressive clothes for life. And when passerbys would mock me, I’d stare back at them and feel sorry. ‘The sexiest people are thinkers,’ Westwood once said.”

Other people and accounts sharing well-chosen (though not personal) photos on Instagram include couture collector Sandy Schreier; performer Justin Vivian Bond; The Vampires Wardrobe; Eurythmics singer Annie Lennox; model Carolyn Murphy; and Diet Prada. Sustainable-fashion company JCRT has the photo of Jordan wearing full Mondrian face with Westwood in a plaid bondage suit. For 1990s runway video, check out Unforgettable Runway, which has multiple clips. It seems appropriate to end with the Business of Fashion’s repost of this 2021 video of Westwood calling out capitalism for creating the climate crisis.

Westwood’s passing reminds me that there were other style icons and influencers who died this year, each of whom I would have liked to dedicate an entire post to. Jordan was one of those, so I’m glad I was able to write about her at some length here. I can only pay tribute to the others briefly and belatedly.

- Elsa Klensch, CNN’s 1980s fashion reporter, died at 92 in March. I was glued to the TV waiting for “Style With Elsa Klensch” to come on, the same as so many other fashion fans of my generation.

- Also in March, Details magazine founder Annie Flanders died aged 82. As I said in 2008, I was obsessed with Details and its coverage of the vibrant downtown scene in the 1980s. I deeply regret not keeping all my copies. The late, great street-style photographer Bill Cunningham was part of the original Details team. Details was how I “knew” Dianne Brill, DJ Anita Sarko, club door gods Sally Randall and Haoui Montaug, designer Stephen Sprouse, model Teri Toye, and so many other people I’ve blogged about. That’s why its bothered me for four years that I never wrote anything about Details nightlife columnist Stephen Saban when he died at age 72 in 2018. He was my guide to all the players. So here’s my extremely late note of appreciation and a link to his New York Times obituary.

- Photographer Marcus Leatherdale was another important member of the Details team. He died this April, aged 69. Around the same time this year, Regine died at 92. She was the club impresario who claimed she created the word “discotheque” when she opened her first Paris club in the 1950s. She had a famous New York hot spot in midtown in the 1970s, with an atmosphere that stood in contrast to the grittier downtown clubs that came in the 1980s.

- Another magazine editor — the Vogue editor between Diana Vreeland and Anna Wintour — was Grace Mirabella, who died in December 2021, aged 92. She bounced back from a classic stealth Vogue firing by creating her own magazine, Mirabella, that published from 1989 to 2000. It was famous enough to get a mention on Family Guy, to my vast amusement. I’ve collected so many wonderful stories about Grace Mirabella that I really should revisit her in a separate post.

- Finally, this January, Peter Hidalgo died aged only 53 in a New York homeless shelter. He played a key part in the brief and brilliant New York career of fashion designer Miguel Adrover in the late 1990s and early aughts. Hidalgo was a co-winner of the Fashion Group International Rising Star award for womenswear in 2010, just two years before I won the FGI Rising Star award for fine jewelry.

Life is unpredictable. Who could have foretold that Hidalgo would fall so hard from his early successes, while Westwood would continue to soar from her start in safety-pinned t-shirts and rubber? All I know is that Westwood was right when she said, “You have a more interesting life if you wear impressive clothes.” Not expensive, mind you. Impressive!

This is wonderful. Thank you!

Thank YOU!

Wonder write up on a fascinating designer and woman who meant alotinthe fashion world…and punk movement.

Thank you xoxo