I haven’t stopped thinking about the Grammys since they aired just over a week ago — and by “the Grammys” I mean “Beyoncé.”

The show belonged to Beyoncé — now the most nominated female artist in Grammy history — even though she only won two of her nine categories: best urban contemporary album for Lemonade and best music video for “Formation.” Her unhurried, highly choreographed, nine-minute medley of the songs “Love Drought” and “Sandcastles” was as much performance art as it was performance, a literal showstopper that brought Lemonade‘s themes of black female power, suffering, and endurance on a historically white stage. Introduced by her mother and bowed down to by her dancers, she was presented as a queen among women.

A golden gown by Peter Dundas and a headpiece incorporating both a halo and sun rays brought to mind a Byzantine empress, a medieval Virgin Mary, and the African goddess Oshun — all of those references heightened by the fact that the singer is pregnant with twins. (The portrait of her own face at the midsection of her gown was a particularly royal touch.) The fact that she sounded as beautiful as she looked has been proven by her isolated vocal track — a dose of reality for people who fault her for being an “entertainer” rather than a “singer.” During Beyoncé’s act, it seemed like nothing could bring down Beyoncé, not even gravity.

Unfortunately, it might be easier to fight gravity than the Grammys’ longtime biases. Beyoncé lost the big awards for song, album, record of the year, and pop solo performance to Adele, who became the first person to sweep album, record and song of the year twice. Adele also won for pop vocal album, meaning she won all five categories in which she was nominated.

This came as a surprise to pretty much no one. Only 10 black artists have won album of the year 12 times since the category was introduced in 1959. (Stevie Wonder won three times, which accounts for the discrepancy in the number of artists compared to the number of awards.) The Grio provided the full list:

- Stevie Wonder – Innervisions (1974) | Fulfillingness’ First Finale (1975) | Songs in the Key of Life (1977)

- Michael Jackson – Thriller (1984)

- Lionel Richie – All Night Long (1985)

- Quincy Jones/Various Artists – Back on the Block (1991)

- Natalie Cole – Unforgettable…with Love (1992)

- Whitney Houston – The Bodyguard: Original Soundtrack (1994)

- Lauryn Hill – The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1999)

- Outkast – Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (2004)

- Ray Charles – Genius Loves Company (2005)

- Herbie Hancock – River: The Joni Letters (2008)

Among the unsurprised? Beyoncé herself. As Lainey Gossip points out, the signs were there. Six days before the awards, an article in the New York Times raised the question of whether some artists, including Beyoncé, were somehow “gaming” the Grammy system. And immediately before the televised show, the Los Angeles Times pointed out that the urban contemporary award wasn’t given out during the non-broadcast part of the awards as it usually is: “That means organizers want to present that award during prime time. And why might that be? Perhaps because they know Adele won album of the year and they desperately want something to give Beyoncé while millions are watching.”

Then, as Lainey Gossip said:

“Another indication that she KNEW was her acceptance speech. Everything she wanted to say was said, written down on a gold card that complemented her outfit … and delivered exactingly so that it would be clear exactly what she was trying to accomplish with Lemonade, so that there would be no missed sentiment, no doubt, about her message.”

This was the message she delivered:

” … We all experience pain and loss, and often we become inaudible. My intention for the film and album was to create a body of work that would give a voice to our pain, our struggles, our darkness and our history. To confront issues that make us uncomfortable. It’s important to me to show images to my children that reflect their beauty so they can grow up in a world where they look in the mirror — first through their own families, as well as the news, the Super Bowl, the Olympics, the White House and the Grammys — and see themselves. And have no doubt that they’re beautiful, intelligent and capable. This is something I want for every child of every race, and I feel it’s vital that we learn from the past and recognize our tendencies to repeat our mistakes.”

This call for awareness was apparently lost on Recording Academy president Neil Portnow, who, in an interview with Pitchfork after the show, said about the awards, “No, I don’t think there’s a race problem at all.” He argued that the 14,000 Grammy voters are professionals who are unaffected by societal bias: “We don’t, as musicians, in my humble opinion, listen to music based on gender or race or ethnicity. When you go to vote on a piece of music—at least the way that I approach it—is you almost put a blindfold on and you listen.”

He inadvertently undercut that idealistic statement when he said:

“It’s a matter of what you react to and what in your mind as a professional really rises to the highest level of excellence in any given year. And that is going to be very subjective.”

And when he said, “We ask that they not pay attention to sales and marketing and popularity and charts,” I felt like he was getting into the territory of alternative facts because it’s obvious that sales and popularity often do matter at the Grammys, just like they do in other contests in other industries. Not always, but often. How else would Mumford & Sons win album of the year in 2013 for Babel (2012 album sales: 1,463,000) over Frank Ocean’s far more critically acclaimed Channel Orange (albums sold by 2014: 621,000).

Sales and popularity frequently coincide with white skin, and the Grammys reflect that. Look at what happens when a white nominee turns up in a traditionally black category, especially if he or she has had massive, mainstream sales success. Eminem, for instance, holds the record for most wins in the best rap album category, with six awards. As an Eminem fan, I don’t hesitate to say that at least one win, for Relapse in 2010, wasn’t deserved (though that album wasn’t as disastrous as some critics claimed). But the most embarrassing example of the white-man grading-curve in the best rap album category came in 2014, when Macklemore’s and Ryan Lewis’s The Heist — an album that had reportedly come close to being classified as pop rather than rap — beat out Kendrick Lamar’s critically acclaimed good kid, m.A.A.d city. Now, I’ve got to admit to my own biases: I’m very pro-fashion and because Macklemore’s infectious “Thrift Shop” is the one of the best clothes-shopping songs and videos OF ALL TIME, I feel like I’d give it best rap song pretty much any damn year.

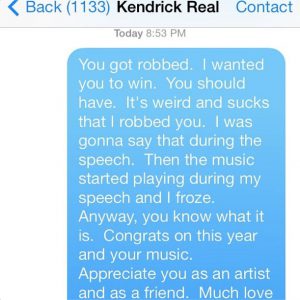

The complete album is a different story. Everyone except the Grammy voters knew Macklemore and Lewis didn’t deserve best rap album, including Macklemore and Lewis. The already awkward situation became even more cringe-worthy when Macklemore acknowledged the unfairness in a private text to Kendrick Lamar, which he then shared via Instagram. (“I think it was uncalled for to be 100 with you,” Lamar later said about Macklemore going public with the conversation.)

The backlash is thought to be one reason why Macklemore and Lewis didn’t submit their 2016 album, This Unruly Mess I’ve Made, for consideration at this year’s Grammys. (The talented Chance the Rapper won best rap album, best rap performance, and best new artist.)

This kind of snub doesn’t only happen in the rap category and it’s far from a modern-day phenomenon. Michael Hann, writing for the Guardian, reviewed some of the worst-ever album of the year choices. One could argue that the worst of the worst came in 1981, when Christopher Cross’s self-titled album beat fellow (white) nominees Barbra Streisand and Barry Gibb, Billy Joel, Frank Sinatra, and Pink Floyd’s The Wall. (The Wall!) Hann points out that black artists who weren’t nominated that year included Diana Ross for Diana, which had two big hits; Teddy Pendergrass for his platinum album TP; and the Jacksons’ Triumph.

Complicating matters is the Grammy voters’ pronounced preference for the unchallenging. Two other albums eligible for those 1981 Grammys were AC/DC’s Back in Black and David Bowie’s Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps). Bowie actually had to die to get any respect from the Grammys: His final album, Blackstar, won all five of the awards it was nominated for in this year’s Grammys, but during his life, he only received one Grammy for best short form video in 1985. That year was exceptional in another way because three of the five nominees for album of the year were black performers, and a black performer won the category. As you saw from the Grio’s list at the beginning of this post, that performer was Lionel Richie, who had a hit with his album All Night Long. Here’s where the trend towards blandness kicks in: Richie beat out Prince’s Purple Rain, Tina Turner’s Private Dancer, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA, and Cyndi Lauper’s She’s So Unusual. Come on! There was no way that Richie had the best album that year — even though without it, we wouldn’t have this fabulous Richie/Adele mashup.

Getting back to Adele — with her big hit album that can be played in drugstores and dentists’ offices without bringing up any uncomfortable racial issues — she simply had to win, same as Taylor Swift did last year when her pop confection 1989 beat out Kendrick Lamar’s hard-edged To Pimp a Butterfly. Adele is deservedly beloved for her big, beautiful, and sometimes unpredictable voice. She’s so endearingly forthright that when she flubbed her dirge-like George Michael tribute during this year’s Grammys, everyone loved her even more for swearing on live TV; referring to the previous year’s technically marred performance; and starting over. (I was charmed too, even as I mused that Adele was supposed to be the superior “singer” to Beyoncé’s “entertainer.”) Thankfully, Adele, who had already complimented Beyoncé in her earlier acceptance speeches, handled the final award diplomatically — perhaps, in part, because she’d had a lesson in what not to do from Macklemore. She called Lemonade “monumental,” and added:

“All us artists adore you. You are our light. And the way that you make me and my friends feel, the way you make my black friends feel is empowering, and you make them stand up for themselves. And I love you, I always have.”

Beyoncé, in the audience, accepted the tribute with emotion.

Speaking to the press after the show, Adele was more blunt, saying of Beyoncé, “I felt like it was her time to win. What the fuck does she have to do to win Album of the Year?” Rembert Browne of Slate has the answer for that in an essay entitled, “For a Black Artist to Win Album of the Year, They Have to Make an Album of the Decade.” He argues that the 12 winning albums by black artists fall into two camps: the very safe (compilations of various artists, cover songs, awards given in recognition of lifetime achievement, Lionel Richie) or ones that are so revolutionary, so massive, so instantly classic as to be undeniable (Stevie Wonder’s three wins, Thriller, Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill).

It seems that Beyoncé needs to do a soundtrack album or the album of a lifetime to get the recognition she deserves. Alternatively, she could take her sister Solange’s tweeted-and-deleted advice: “create your own committees, build your own institutions, give your friends awards, award yourself, and be the gold you wanna hold my g’s.” Personally, I don’t see Beyoncé staying away because she’s too big and she will win one of these days. But it’s possible that other major artists could follow Frank Ocean’s lead. He didn’t submit his newest album, Blonde, for Grammy consideration, calling the awards dated: “That institution certainly has nostalgic importance,” he told the New York Times. “It just doesn’t seem to be representing very well for people who come from where I come from, and hold down what I hold down.”

Neil Portnow of the Recording Academy should be more alarmed than he seems to be. You can only have an A-list event if A-list people attend. What happens if black performers follow Ocean’s lead and Solange’s suggestion and refrain from participating because they feel they won’t get their due … while, at the same time, more white performers take a page from Macklemore and stay away to avoid an undeserved win that turns into humiliation? (I’ve wondered whether Eminem sometimes skips the ceremony due an embarrassment of riches.) I’ll tell you what happens. You’ll end up giving a lifetime achievement award to Christopher Cross, and no one is going to tune in for that. (Sorry, Chris!)

You have just written why I have given up on all award shows. I always feel that those most deserving never win.

I would like to know why I used to like Adele voice. Now it grates on my nerves like nails on a blackboard. There must be some change to it that I just can’t pinpoint. I can still listen to her last album just fine. Weird, ain’t it? Only thing is that I have phenomenal hearing so it is probably just me.

Speaking of weird. I heard a song in the grocery store the other day. Thought it was Miley Cyrus, but singing in her Hannah Montana/not quite grown up voice. Shazamed it next time it I hear it – Lady Gaga? WTF? Are they tuning these people up? But backwards?