A fascinating article by Eileen Pollack in Sunday’s New York Times Magazine asks, “Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science?” It’s worthwhile reading for all wimmins, even those not interested in science, and I’m going to get to why that is … just as soon as I tell you about the science part.

Pollack was one of the first two women to earn a bachelor of science degree in physics from Yale. She graduated summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa in 1978, despite having attended a rural public high school where she had to teach herself calculus because she wasn’t allowed to take the few accelerated math and science courses. Yet, after all that, she didn’t pursue physics as a career (she’s now a professor of creative writing at the University of Michigan). “Not a single professor — not even the adviser who supervised my senior thesis — encouraged me to go to graduate school. Certain this meant I wasn’t talented enough to succeed in physics, I left the rough draft of my senior thesis outside my adviser’s door and slunk away in shame,” she writes.

She returned to Yale in the fall of 2010 to see if and how things had changed. At the time, the chairwoman of the physics department was an astrophysicist named Meg Urry, with a Ph.D from John Hopkins and a postdoctorate from M.I.T.’s center for space research. When Yale hired Urry as a full professor in 2001, she was the only female faculty member in the department. In 2005, after Lawrence Summers, then the president of Harvard, seemed to hypothesize that innate differences between men and women kept women back in the science and math fields, Urry responded with an op-ed in the Washington Post. She wrote that discrimination isn’t always blatant:

“It’s the slow drumbeat of being underappreciated, feeling uncomfortable and encountering roadblocks along the path to success.”

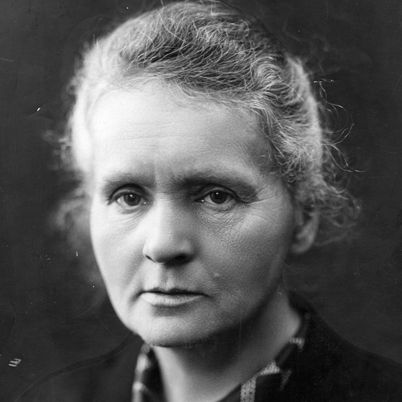

Meg Urry, professor of physics and astronomy at Yale, photographed by Joseph Ow for The New York Times.

Pollack’s article goes on to give examples of both kinds of discrimination: the in-your-face type and the more subtle, sometimes nearly invisible-because-it-is-so-accepted type. Family concerns shouldn’t really be a reason for women to give up, says Urry, who notes that “being an academic provides a female scientist with more flexibility than most other professions,” Pollack writes. (Urry says at another point in the story about a male professor saying academics is a “very hard life”: “They’re their own bosses. They’re well paid. They love what they do.”) Urry, who describes an “equal relationship” with her own husband who doesn’t say “he’s helping” when he looks after their kids, “suspects that raising a family is often the excuse women women use when they leave science, when in fact they have been discouraged to the point of giving up.” Pollack says:

“All Ph.D’s face the long slog of competing for a junior position, writing grants and conducting enough research to earn tenure. Yet women running the tenure race must leap hurdles that are higher than those facing their male competitors, often without realizing any such disparity exists.”

In the mid-1990s, there was an investigation at M.I.T. instigated by three female professors who felt their careers had been limited by such hurdles. The investigating committee found “differences in salary, space, awards, resources and response to outside offers between men and women faculty, with women receiving less despite professional accomplishments equal to those of their colleagues.” Have things changed since then? Not as much as you’d hope. Pollack notes:

“In February 2012, the American Institute of Physics published a survey of 15,000 male and female physicists across 130 countries. In almost all cultures, the female scientists received less financing, lab space, office support and grants for equipment and travel, even after the researchers controlled for differences other than sex.”

And at Yale, Pollack’s alma mater, a study started in 2010 and published last year had researchers send out identical resumes to professors of both genders ostensibly on behalf of a recent undergraduate looking for a position as a lab manager. Half the 127 faculty participants received a resume from “John.” Half received a resume from “Jennifer.” The job application was good but not kick-ass. It came with letters of recommendation and the co-authorship of a journal article but both “John” and “Jennifer” had a grade point average of only 3.2 and had withdrawn from one science class. Each professor was asked to rate John or Jennifer (on a scale of one to seven) on competence, hireability, likeability, and the faculty member’s willingness to mentor the candidate. Then the professors were asked to choose a salary. The results:

“No matter the respondent’s age, sex, area of specialization or level of seniority, John was rated an average of half a point higher than Jennifer in all areas except likability, where Jennifer scored nearly half a point higher. Moreover, John was offered an average starting salary of $30,238, versus $26,508 for Jennifer.”

The authors of the study weren’t surprised that female professors were as hard on Jennifer as the male professors. Those results are similar to other studies that have found that biases stem from “repeated exposure to pervasive cultural stereotypes that portray women as less competent by simultaneously emphasizing their warmth and likability compared to men.” Women AND men are affected by those cultural ideas.

Jo Handelsman, one of the Yale researchers, was most bothered by the mentoring issue. That’s where Urry’s “slow drumbeat of being underappreciated” comes in. Handelsman mused:

“If you add up all the little interactions a student goes through with a professor — asking questions after class, an adviser recommending which courses to take or suggesting what a student might do for the coming summer, whether he or she should apply for a research program, whether to go on to graduate school, all those mini-interactions that students use to gauge what we think of them so they’ll know whether to go on or not. . . . You might think they would know for themselves, but they don’t. …Mentoring, advising, discussing — all the little kicks that women get, as opposed to all the responses that men get that make them feel more a part of the party.”

The “little kicks” are familiar to me. There was the high-school English teacher who asked me, “Why are you reading books by women?” when he saw me reading Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte. At one of my first jobs, I was passed over for a promotion in favor of a guy who was completely inept. When I furiously challenged my boss, my boss stammered for a while and finally said of the incompetent employee, “Well, he’s older and has a family.” That was the same job that took place in a nasty, brutish environment run by men. For the first year, I went home crying nearly every night after being yelled at all day. The best way to survive was to act as bad-ass as the male managers. A couple of years later, a guy who worked with me at that place tried to knock me out of the running for another job by saying I was too mean, as if I had created the awful atmosphere rather than been hurt by it. I happened to be looking for a new job because I needed to escape an old job that became miserable after a male manager had spread a rumor that I’d slept with another male manager to get the gig. A few more corporate jobs down the line, I worked at the notorious investment bank Lehman Brothers, where the only female managing director I personally encountered was in human resources. Human resources is, of course, a non-revenue-producing part of a company. At Lehman, only the revenue producers had real power, which they used to bankrupt the company. These days, some people (male and female) judge the newsworthiness and salability of my jewelry line based on their feelings about and relationship to my journalist husband.

Acknowledging such obstacles and using that knowledge to push on is crucial. In my corporate days, I spurred myself on to ask for promotions and raises — even when I felt shy or scared or like I would be turned down — by reminding myself that the men around me never hesitated to ask, no matter how average or downright undeserving they were. Pollack has a good anecdote of that sort in her New York Times story. This happens to be about a physics department, but it could be about any working environment:

“One student told [Meg] Urry she doubted that she was good enough for grad school, and Urry asked why — the student had earned nearly all A’s at Yale, which has one of the most rigorous physics programs in the country. ‘A woman like that didn’t think she was qualified, whereas I’ve written lots of letters for men with B averages.”

That kind of mindset is one that I’ve dealt with for a long time, but, in the past couple of years — trying to make it in a competitive, expensive creative field during a recession — I’ve realized that there was a whole new attitude I needed to learn: not to take setbacks as catastrophes. I think women are, more often than men, encouraged to give up when the going gets tough. Looking at the persistently low numbers of girls taking advanced physics classes, Pollack writes “Maybe boys care more about physics and computer science than girls do. But an equally plausible explanation is that boys are encouraged to tough out difficult courses in unpopular subjects, while girls, no matter how smart, receive fewer arguments from their parents, teachers or guidance counselors if they drop a physics class or shrug off an AP exam.” She then told the following story, which was the one that really jumped out at me. Pollack got a 32 on her first physics midterm during her freshman year at Yale. Her parents encouraged her to switch majors and off she went to ask her professor, Michael Zeller, to sign her withdrawal slip. Zeller asked her why she wanted to drop a course over a midterm when he’d gotten D’s in two of his physics courses. “Not on the midterms — in the courses,” Pollack writes. “The story sounded like something a nice professor would invent to make his least talented student feel less dumb. In his case, the D’s clearly were aberrations. In my case, the 32 signified that I wasn’t any good at physics.”

How many of you recognize that thinking? “Yeah, s/he had this failure, but that was a freak thing. My failure proves I’m no good”? It’s a pretty common reaction and, unfortunately, there’s not always a sensible professor/colleague/family member/whoever around to tell you how ridiculous is is. That’s when you have to remind yourself of a quote questionably attributed to Winston Churchill, but useful regardless of the source: “Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.” Pollack lucked out in the case of her failing midterm. Zeller didn’t sign off on her course change. “Just swim in your own lane … You can do it … Stick it out,” he told her. Pollack earned a B in the course and an A the following semester. (Later, however, when Pollack told Zeller her dream was to continue studying at Princeton, he shook his head and said if she went there “you had better put your ego in your back pocket, because those guys were so brilliant and competitive that you would get that ego crushed, which made me feel as if I weren’t brilliant or competitive enough to apply.” And it was only while she was working on this story, decades after the fact, that Pollack found out her senior thesis adviser considered her project exceptional.)

There’s more proof of the benefits of believing in yourself despite all odds in another story in the Times magazine. This one is by Fred Vogelstein, adapted from the coming book Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution, about Steve Jobs’s introduction of the Apple iPhone during a live demonstration at a Macworld trade show. It was done with more chutzpah than working technology:

“It’s hard to overstate the gamble Jobs took when he decided to unveil the iPhone back in January 2007. Not only was he introducing a new kind of phone — something Apple had never made before — he was doing so with a prototype that barely worked.”

There was no production line. Only 100 iPhones existed. Some of them looked really bad. The software was full of bugs: “The iPhone could play a section of a song or a video, but it couldn’t play an entire clip reliably without crashing. It worked fine if you sent an e-mail and then surfed the Web. If you did those things in reverse, however, it might not.” Jobs insisted that the demonstration had to go just so, and it did, although the “iPhone project was so complex that it occasionally threatened to derail the entire corporation.” During his product introduction, Jobs said, “This is a day I have been looking forward to for two and a half years.” And that’s from a guy who had to be convinced to do a phone in the first place.

Obviously, we’re not all rocket scientists (though “You don’t need to be a genius to do what I do,” says Meg Urry, reassuringly) or Steve Jobs. But there are a lot of failures hidden in any success story that all of us can take inspiration from when we need something to keep us going. There are going to be times the only person on your side is you, especially if you’re a woman or a minority. If the world is against you, you don’t have to agree with the world. And when, at last, you’re a big success, don’t forget to help other people who are hearing the same negative messages you did. Just because you overcame them doesn’t mean everyone else can. Be the person who says, “Stick with it.”

An aside to my aspiring clothing-designer friends: reread iPhone production line paragraph and then take this advice: When a store asks you, “Can you produce these items if we order them?” the only answer is “Yes.” Not, “Yes, but …” and an explanation. Just “Yes.” You’ll figure out how to do it later … or maybe you’ll fuck up and the store will never work with you again. At least you won’t have talked yourself out of the opportunity by saying “I don’t know.”

Direct links to both New York Times articles

“Can You Spot the Real Outlier?” (the title in the hard copy of the magazine) by Eileen Pollack

“And Then Steve Said, ‘Let There Be an iPhone’” by Fred Vogelstein

Thank you for posting this! I have been thinking a lot about Pollack’s article since I read it last week and I think it’s great that you are talking about it.

In terms of sexism in the business world, I found this recent article about HBS to be equally depressing but interesting: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/08/education/harvard-case-study-gender-equity.html?pagewanted=all

Oh yeah! I read the Harvard story. If Harvard is truly worse than any trading floor…I mean, that’s worse than I can even imagine! Trading floors for me (as they used to be) epitomize a bad biz environment!

I read the NYT article too and have been thinking a lot about it. My husband is a scientist, and women in his program (late 1970’s) were exceedingly rare. I chose the “soft” science of psychology and never considered the STEM professions — but I wonder if I would if I were 20 yrs old now? It’s exciting work.

Definitely more exciting work now than it was! I remember when my father (a programmer with a degree in Electrical Engineering) had a computer that took up a full wall in his office.

Wendy –

Thanks for this amazing article & commentary on what is (unfortunately) a truly pervasive & stinky problem in our supposedly “forward” society.

I am a feminist at heart & thus have always pushed myself in areas where men are supposed to dominate. But, when that complete stranger (guy) looked at me & told me there was NO WAY I was smart enough to go to MIT because I was blonde, I was going to try no matter what!

I found out that, yes, I am good at math & economics & business & statistics. But, no, I am really not good at Science. =)

You are so right about the business world & that is why I have never wanted to work for big business & have always wanted to own my own company.

I have read a lot of books about surviving as a woman in business, from “The Girl’s Guide to Being a Boss (Without Being a Bitch)” to, “Cracking The Boy’s Club Code: The Woman’s Guide to Being Heard and Valued in the Workplace”.

None of those books really had the answer to the ultimate question:

Why should we, as women, have to resort to behaving as something other than we are (feeling, understanding, usually nice) to actually be respected & treated equally & fairly in businesses that actually PAY?

The best business book I ever read is called “Bury My Heart At Conference Room B” by Stan Slap. It was funny & actually a really good read. It also promotes engaging employees by encouraging them to bring their whole selves to work – including their feelings & emotions (imagine that!)

I love this part of your blog especially:

“When a store asks you, “Can you produce these items if we order them?” the only answer is “Yes.” Not, “Yes, but …” and an explanation. Just “Yes.” You’ll figure out how to do it later … or maybe you’ll fuck up and the store will never work with you again. At least you won’t have talked yourself out of the opportunity by saying “I don’t know.””

Just “Yes.” Just “Yes.” Just “Yes.”

Hell Yes, Wendy. Amen, sister.

I’m determined to read the Stan Slap book now. Thanks for the recommendation and your thoughtful comment.

What you said in the paragraph starting “Why should we, as women…” made me think again of this part of the NY Times article: “‘The boys in my group don’t take anything I say seriously,’ one astrophysics major complained. ‘I hate to be aggressive. Is that what it takes? I wasn’t brought up that way. Will I have to be this aggressive in graduate school? For the rest of my life?'”

Because I’m so used to the nasty environments and have internalized all the “rules,” at first I was like, “Duh, of course, you have to be tough to get ahead. That’s life.” But then I realized …who said everything has to be so nasty? Does astrophysics really have to be cutthroat? Is there an objective reason for that? Interesting!

Interestingly though, I’ve also gotten plenty of grief from the other side of the coin. Being naturally assertive and outspoken, I’ve been told I’m “too aggressive” more times than I can count (thankfully not as much as I’ve moved up the ranks, and never at my current job). As if anyone would ever say that to a man! So apparently we’re supposed to be demure and sit quietly by while less qualified men get more opportunities than us. Don’t be too feminine, but don’t stand up for yourself either!

Oh yes, that’s always the other problem. That was totally my problem at various workplaces. You can’t be quiet and you can’t be strong!

Really excellent piece Wendy. The Pollack piece was great too. I already knew about much of what is covered in the Vogelstein piece.

Pollack’s experience reminds me very much of my own experience. I received no encouragement from anyone to pursue my Computer Science interests until I was employed as a Technical Writer at Adobe after graduating from SUNY Albany with an English major and Computer Science minor. It was Adobe Computer Scientists, some of the best in the world at the time, who encouraged me to pursue Computer Science and helped me succeed there as a software engineer. That’s why I hoped to pursue a graduate degree in Computer Science after leaving Adobe in 2003 due to severe tendonitis in both hands. As it turns out, my hands weren’t quite up to it — you can’t get away from intensive keyboarding even pursuing an academic path. In retrospect, I should have pursued a graduate degree in Mathematics or Physics.

When we met you in NYC I mentioned meeting Martin taking a course in Physics (to prepare for the MS in CS). He was the very first professor who ever encouraged me to succeed in a hard science course. My previous mathematics teachers and professors were okay but uninspiring when it came to interactions and encouragement, and previous science teachers and professors were all awful.

Martin’s course was the hardest course I ever took in my life, because I wasn’t brought up to physically work with things like tools and lab equipment. I kept fumbling everything and had a difficult time mapping the physical to the abstract, for example, seeing that a projectile in 3-D space is represented as an abstract vector. I got vectors, just not that relationship. I worked on that course 40-60 hours a week. After labs, I would un-tape butcher paper with the marks where the projectiles landed from the lab table and recreate the whole setup in my kitchen at home so I could study it for hours.

I got an A.

It feels like so much of my life has been about overcoming discrimination.

Wow, your comments about the physical work could have fit right into the NYT story. I thought it was interesting how women came in with less experience in that area but were able to catch up.

I remember your story with Martin! And I think I told you that I wound up married to the guy who was most supportive of my career too!

I was like, “Figures. I’m looking for a mentor and I wind up with a husband.” Things always work out strangely for me!

I can’t think of a better way to find a husband.

Wow, that was a lot of reading – good reading! “Yes.” Excellent post.

Say “yes” and worry about the consequences later! LOL.

Great piece, Wendy. I never knew you worked in banking.

We still have a long way to go. But did you hear that Janet Yellen is being named Fed chair? So that’s something.

I was in a non-revenue producing side of Lehman, so I was completely unimportant!

Yeah, been following the Yellen coverage. She seems like a very interesting person!

Another great post. But there is one thing missing and that’s the name of the newspaper that put you down for years just because you were a female and heads above the male assholes. So everyone knows, here it is – the Wall Street Journal. They may know finance but they don’t know people.

The managing editor there was awesome though! 😉

Your Dad is awesome too :).

I can recall only one thing he did right.

You’re going to get yourself in trouble! 😛

This is so great. Really glad you posted it 🙂

🙂

Great article, thanks for the post.

A point of pride for my husband is that his mother was in the first class at Cornell that had women graduate with a degree in chemical engineering. There were three of them.

A milestone for sure.

And I’m proud to be the aunt of a beautiful and brilliant niece who switched from being an acting major to biology and is now getting her PhD in biology at Boston U.

You’ve got some amazing family members!

And friends! 😉

Great piece (as always) x

Thank you!

Sorry this is late … am behind on my Wendy reading!

…and in the first year of my doctoral program I remember practicing what we/female grad students called the “ten year old Presbyterian” look (no offense to Presbys) when confronted by several male faculty members coming on to us. You didn’t dare confront male faculty because they had absolute power over female students … and they were skilled enough at crafting their language that if/as perps they would have walked away from any investigation … getting through graduate school wasn’t only about content and expertise … it was about navigating male waters as well. I was a good swimmer … completed the program and earned the degree.

Regarding, YES. Women feel the need to explain, justify, etc., men don’t. In one of my “real world” jobs in a real estate development office I observed negotiations as played by lenders, contractors, subs, etc. Fascinating stuff. I decided use what I learned when I was up for review. With a 50/50 chance I asked for a 33% raise. I simply made a clear request with no follow-up, no explanation, nothing. I sat there, in the full, upright and locked position, eyes on his face, and said nothing. I watched as his face turned red followed by mumbling, stuttering and sputtering as he worked his adding machine … and said, YES! Can’t say it was easy … didn’t think I had a chance … simply wanted to try on the behavior and see how it felt.

Too bad the company went under before the raise came through … but the approach worked. And it felt good … not because I was aping the “Y” but because I was standing in my own truth … breaking a habit, as it were, that I wasn’t aware I even practiced until I watched how the boys played … explaining felt normal, it seemed so “natural.” Ha!

LOVE the story about asking for a raise! Very impressive. And the fact that you picked up on how to do it by watching what was going on around you.

Explaining is a habit that’s hard to break!

All so very very true. Will be forwarding this to everyone I think…including my future sciences professional niece.

You presented all this really well – seriously, thanks. I will be mulling this and your advice for a while. You should write a book, lady. I could have used the career advice a few decades ago. I took defeats waaay too hard. We women allow ourselves to get derailed easily….and because most of the time we are encouraged to. Sad :/

I’ve been working verrrrry sloowwwwlllly on my book, but I need to pick up the pace!